The Favourite is an absurdist and almost parodical take on a historical biopic, directed by Yorgos Lanthimos (also known for The Lobster and The Killing of a Sacred Deer). The film examines the power play in English politics during the reign of Queen Anne (who ruled between 1702 and 1707), specifically between the three most powerful women in the country: Queen Anne herself, her lifelong friend Sarah Churchill, Lady Marlborough, and Abigail Hill, a cousin of Sarah Churchill’s who comes to live at the palace and rises through the ranks to be at the Queen’s ear. It is a story of manipulation, power play, greed, politics and gender, all set amongst a deceptively modern picture of 18th century royalty. Lanthimos paints an incredibly captivating and emotional portrait of these historical figures, but some have questioned how accurate his portrayal of a very real past is, and whether the accuracy of the events told really matters in the context of the film.

On the surface, the film seems to explicitly deal with the intricacies of politics, and perhaps how there could be links between politics from 300 years ago and those of now. Lanthimos explores the concept of domestic versus foreign issues, as Queen Anne’s government squabbles over whether to continue the war with France and run the risk of rebellion and domestic conflicts. It would be easy to assume the film has allusions to the issue of Brexit and Britain’s turbulent relationship with the European Union (as the film came out in late 2018/early 2019 and is a British production); the film seems to have echoes of how Theresa May tried (RIP Teresa’s career) to hold together a similar squabbling government in the face of domestic and foreign issues. However, the project was in development for over a decade and has a Greek director, and so probably does not contain overt allusions to Brexit. The real issue the film speaks on, particularly to modern audiences, is that of gender.

The film provides an incredibly interesting and modern perspective on gender politics and history. Historically, women were considered subordinates and generally less fit than men to rule (hence we’ve only had 5 regnant queens of England; 6 if you count Matilda, which many historians do not), and only in 2018 was a royal inheritance law changed by Queen Elizabeth, meaning that Princess Charlotte now remains ahead of her younger brother Prince Louis in line to the throne. The English history of gender politics and attitudes towards gender in the royal family is completely subverted in this film. From first glance, it is made completely clear that it is women that have all the power (the queen in an official capacity, Lady Sarah Churchill in a literal one, and Abigail Hill in an ambitious and manipulative one), and fighting over total control of the country.

However, Lanthimos also reflects this in other aspects of the film; not just in the meta-narrative. For example, the use of violence in the film is particularly interesting in the way it demonstrates gender balance and power. Any time an act of violence is committed by a male character, it is portrayed as ridiculous and silly, such as rugby tackling and pushing other characters down a hill. On the other hand, when a female character does something violent, it is much more grotesque and has very real and serious consequences. The female characters in the film do things such as poison each other, abuse animals, shoot birds for sport, slap, kick and throw things at each other, hurl verbal abuse and derogatory language and one character even tricks another into putting her hands in bleach. This truly subverts modern expectations of female behaviour in the 18th century, as women are often portrayed as demure and peaceful figures with no free will of their own. This is not only shocking and compelling to modern audiences, but is also almost relatable, as women watching will recognise the refusal of the female characters to conform to the classical image of femininity in themselves, making the film’s portrayal of gender and violence even familiar.

The comparison, too, sheds new light on the way men are historically portrayed: as chivalrous, daring and aggressive. However, Lanthimos amplifies the ridiculous nature of the male behaviour until the audience recognises it as something else – not innate behaviour, but a performance – which could be described as performative chauvinism. This portrayal of male violence certainly has a place in today’s society – Lanthimos adds to the current conversation on rape culture and the notion that “boys will be boys” with his suggestion that male aggression is not natural and innate, but in fact something performed as part of a perceived gender role. He also particularly emphasises the idea that politics is often “a boys’ club” – with subtle nods to societies such as Oxford University’s Bullingdon Club, of which prominent Conservative politicians David Cameron and Boris Johnson were a part, and which modern audiences will certainly recognise in their own concepts of politics. This is summed up particularly succinctly in one scene where many male characters are hurling tangerines at a naked man, all of them laughing – through this, Lanthimos highlights the pettiness and unimportance of the playful yet still violent male behaviour as he juxtaposes it with the serious and clever political power play between the female characters.

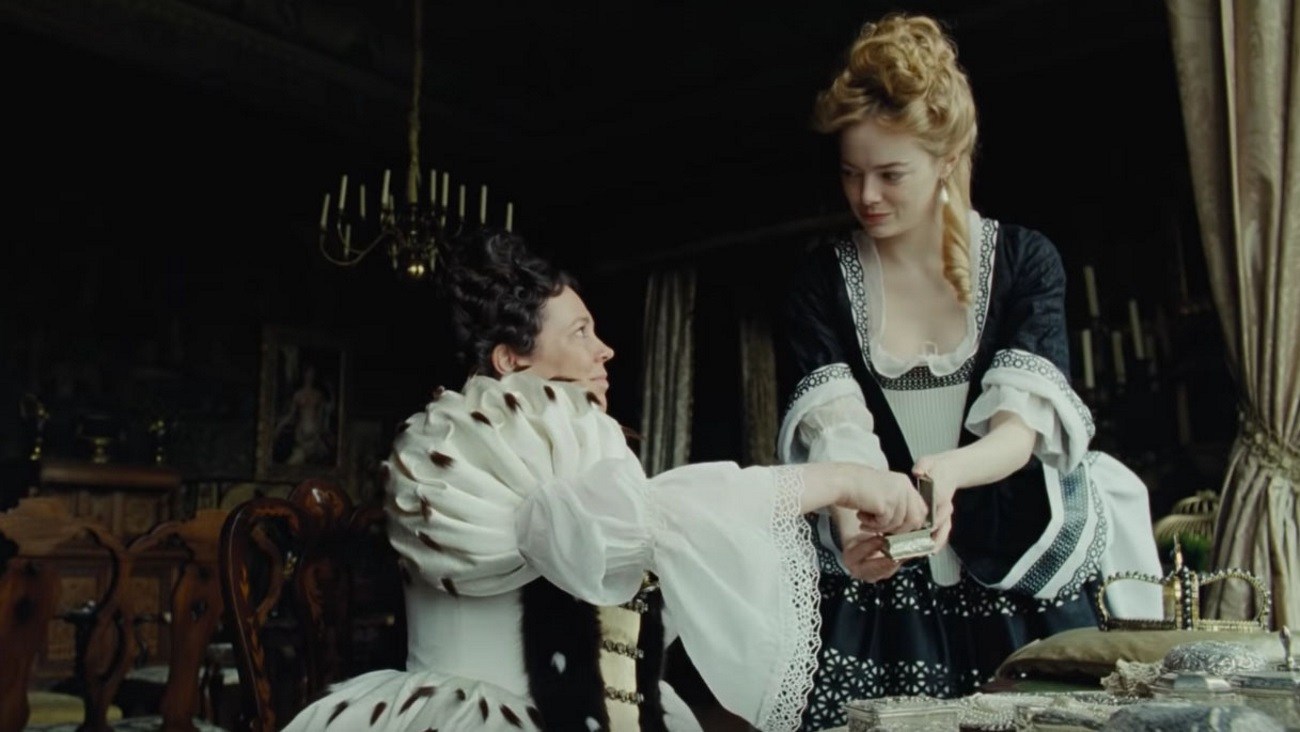

He also skews modern perceptions of gender by having the male characters wear the most extravagant wigs and the most avant-garde makeup, whereas for the most part the female characters go makeup free and actively reject the ideas of wearing ridiculous clothing which would have been typical of the time. In fact, in one scene, Emma Stone’s character Abigail forcibly removes the makeup of her suitor, stating she prefers him without it.

The subject of the costumes themselves is an interesting one, as Lanthimos and his collaborator, costume designer Sandy Powell, actively used anachronistic materials in the costume design. For example, the servants’ costumes are made from denim, whereas Emma Stone’s character frequently wears dresses made of glossy leather. This obvious anachronism can be seen in many other aspects of the film, such as character behaviours, language and movement, such as the ridiculous and modern dance between Rachel Weisz and Joe Alwyn’s characters, and the frequent usage of modern curses. The ‘c-word’ is used often in the film in a derogatory context, as well as modern derivations of it; whereas Mark Morton describes it in his book ‘The Lover’s Tongue’ as only taking on a vulgar meaning in the late nineteenth century.

Lanthimos also uses the technical aspects of the film to remove the audience from a historical setting which they hardly recognise anyway, by using modern cinematographic techniques such as tracking and panning shots and even fisheye lenses, most commonly seen in nineties rap videos. This serves to only heighten the emotional atmosphere of tension and ridiculousness Lanthimos is creating, and does not detract from a historical understanding of the film. The obvious anachronism of the aspects of the film by Lanthimos and his team is a fascinating one, as it directly contradicts the attempts of most other period pieces to be historically accurate. However, the choice works here, as Lanthimos instead uses the recognisability of raw human emotion and circumstances to make the past more accessible and comprehensible to audiences. He deftly undermines the perceived rule in cinema that to create a portrayal of history, one must have accuracy in every detail, and he rejects this so emphatically that it does not detract from the film, but instead serves to make it an engaging and fascinating look into the human condition and our shared experiences, despite a separation of 300 years.