When the Spanish conquistador Pizarro crushed the Inca rebellion in 1537, ‘the conversion of the local population to Christianity was set forth as the essential mission of Spanish imperialism and its legitimation [and] the priests worked to extirpate the native beliefs, destroying the Inca temples and shrines and prohibiting their ritual practices,’[1] highlighting that the initial aim of Spanish missionaries was to replace indigenous culture with Catholicism.

Historian Christine Beaule further adds that ‘the Spanish Colonial system also imposed European modes of town planning, work schedules, writing and civil administration, and of course, the Catholic religion, on Andean indigenous peoples,’ one of the main aspects of which was choosing only ‘a few indigenous languages in which they would teach communities the principles and rituals meant to essentially substitute for indigenous religious ideologies and theologies’ and thus erasing hundreds of other native languages and customs. These linguistic and cultural barriers inhibited the Spanish missionaries in their goal of mass-converting the huge, culturally heterogeneous population of the now-fallen Incan Empire, which itself had conquered and assimilated multiple ethnic groups and tribes across South America, and so the role of art, a universal language, was key to their mission. According to the Museo de Arte de Lima, ‘genres such as easel painting, polychrome sculpture, or engraving —which had no Pre-Columbian precedents— allowed for the didactic depiction of sacred scenes or complex dogmas useful in teaching a new faith to an indigenous population lacking a tradition of writing,’ and this need for art as a religious catechism, combined with pre-Colonial Inca beliefs and cultures, manifested itself in the uniquely-Andean depictions of the àngeles arcabuceros.

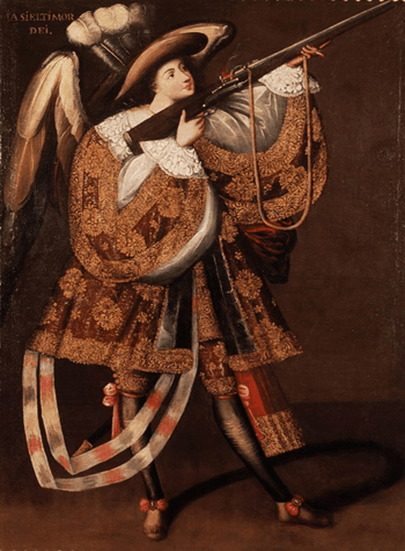

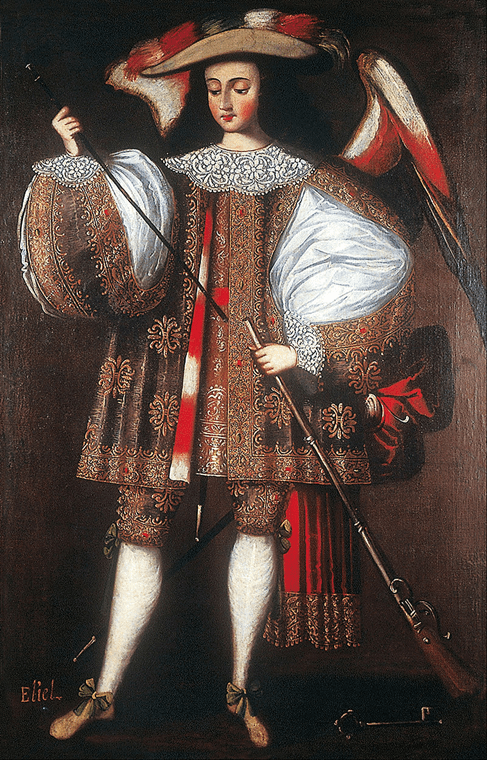

The àngeles arcabuceros are a series of works painted by Inca artists, originating from the colonial period in Spanish Peru, portraying a version of Catholic angels, holding specific models of Spanish guns from the fifteenth century and dressed as local Andean nobles.

The style of the paintings and their inspirations are a clear representation of the assimilation of Inca and Spanish culture in Viceregal Peru. The specific poses of the angels, in the various stages of loading and firing a gun, at first seem curious, but these poses of the subjects may have been heavily inspired by and perhaps even directly copied from engravings in Dutch artist Jacob de Gheyn’s military manual, Wapenhandelinghe van Roers Musquetten ende Spiessen, designed to instruct soldiers how to load and fire weapons through a series of picture plates. First published in Dutch in 1607, the manual was incredibly popular across Europe, and was translated into multiple languages in its subsequent publications. Although it is unclear if Wapenhandlinghe was ever translated into Spanish, Nina Lamal suggests that the Dutch had the monopoly on military publications in Europe and ‘the Antwerp presses had close connections with the Spanish book market,’ suggesting that de Gheyn’s works would have been easily accessible to the Spanish military. These manuals may have been brought to Peru by Spanish soldiers or missionaries as part of their military equipment throughout the seventeenth century, coinciding with the establishment of àngeles arcabuceros as a unique genre from the 1680s. There are certainly undeniable similarities in the poses between de Gheyn’s engravings and the paintings produced by the Inca people, as shown below, even down to the position of the feet and hands.

The most notable differences between the two images, however, are obviously the art style and the subjects’ clothing. The àngeles arcabuceros were stylistically inspired by the works of Spanish painter Francisco de Zurbaran, a leader in religious art patronage in Seville, with his paintings of religious and biblical figures set against plain, dark backgrounds, very similar to their Incan counterparts. Crucially, Anne Sutherland Harris indicates that much of his work was sent by his studio overseas to Spanish colonies in South and Central America, where they clearly inspired the Inca painters of religious art. Zurbaran’s style was important in Spanish religious art for its reverential and simple style, which, according to Sutherland Harris, ‘marries dignified simplicity with powerful forms rendered in a gentle light against a background of impenetrable darkness.’ This style was not only devotional and appropriately pious, but also easy to recreate for the Peruvian artists replicating this style, and was recognisable to the Spanish missionaries. Zurbaran also portrayed his angels as weaponised, as opposed to winged cherubs or a heavenly choir, a further influence on the àngeles arcabuceros.

However, the Andean àngeles arcabuceros were still uniquely set apart from the Spanish religious paintings of artists like Zurbaran, especially in the clothing and iconography of the subjects portrayed. These angels were not only shown brandishing Spanish harquebuses, as opposed to Zurbaran’s Michael with his flaming sword and pointed shield, but were also dressed in local Andean fashion, specifically that of Andean nobles, whose clothing symbolised a fusion of indigenous traditional elements and imported Spanish styles. One of the main differences in these Andean fashions and those of European Spaniards were the textiles used. In the clothing of the àngeles arcabuceros, according to Kate E. Holohan and Andrew W. Mellon from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, ‘red is the predominant colour; this is typical of Andean textiles both before and after the sixteenth-century Spanish invasion, and was probably achieved through the use of dye extracted from cochineal, an indigenous American insect.’

<p class="has-drop-cap has-normal-font-size" value="<amp-fit-text layout="fixed-height" min-font-size="6" max-font-size="72" height="80">Furthermore, the particular pattern of the textiles worn by the angels seems to include depictions of red <em>ñucchu </em>flowers, which were considered sacred by the Inca, but have also featured heavily in Christian religious festivals in South America, such as Holy Week and Corpus Christi, since the Spanish conquest. In both characteristics of the textiles – its red colour and the pattern of <em>ñucchu </em>flowers<em> – </em>there is a suggestion of hybridity and assimilation between Inca and Spanish culture, and a continuity from traditional native clothing which was retained into the Viceregal period, especially with the transformation of the <em>ñucchu </em>flower as sacred to Inca people and then to Christian beliefs.Furthermore, the particular pattern of the textiles worn by the angels seems to include depictions of red ñucchu flowers, which were considered sacred by the Inca, but have also featured heavily in Christian religious festivals in South America, such as Holy Week and Corpus Christi, since the Spanish conquest. In both characteristics of the textiles – its red colour and the pattern of ñucchu flowers – there is a suggestion of hybridity and assimilation between Inca and Spanish culture, and a continuity from traditional native clothing which was retained into the Viceregal period, especially with the transformation of the ñucchu flower as sacred to Inca people and then to Christian beliefs.

The style and structure of the clothing itself also reflects this duality of culture in the Andean nobility, beyond just the textiles. In the pre-colonial Andes, men wore woven tunics with geometric patterns known as unkus, which they continued to wear after the Spanish invasion, but with some adaptations: Christine Beaule writes that ‘post-conquest unkus are generally more elaborately decorated than their precolonial counterparts […] Decorative motifs changed from largely geometric ones to include insects, butterflies, quatrefoils and flowers […] These changes in the decoration of unkus were influenced by European brocade.‘

She also suggests that ‘the unkus were often further elaborated by the addition of flowing lace sleeves’ as can be seen in all three paintings, and ‘the costume was Hispanized […] by the addition of breeches underneath that end at the knee, and with a fringed band of cloth […] encircling the leg at the knee (a pre-Hispanic Inka accessory)’, as the Spanish considered the loincloth or wara traditionally worn under the unku to be inappropriate. According to Beaule, ‘the overall effect of pairing a shortened tunic over breeches was to turn the unku into a Spanish carniseta (a long, loose-fitting shirt),’ a further example of the hybridisation of Spanish and Inca culture. These trans-cultural Andean outfits were widely reflected in religious art at the time, not only in the àngeles arcabuceros but also in ‘festivals of the Virgin Mary, paintings of Corpus Christi festivals and religious art throughout the Colonial period; in some early seventeenth-century churches, wooden images of Christ were dressed like Inca rulers.’ Beaule argues that ‘clearly these hybrid uses of an indigenous garment reflect their widespread acceptance as not only symbols of indigenous identity, but as more general indicators of indigenous political authority and social status,’ representative of a wider pattern of assimilation and compromise as part of the Spanish missionaries’ conversion strategies. Crucially, ‘continued use of unku was treated with indifference by colonial authorities and was seen as far less threatening to the social order than continued worship of huacas (sacred places and objects on the landscape) which was viewed as idol worship and therefore sacrilegious:’ essentially, the Spanish missionaries were willing to allow a continuation of certain indigenous cultures so long as it did not conflict with the overall goal of converting the religion of the local people, and this attitude was paired with practices of destroying Inca temples. However, Alphonso Lingis suggests that even these attempts by Spanish missionaries to completely replace Inca beliefs and religion were somewhat unsuccessful, as the they built their new Catholic churches over the same spots they had destroyed Inca temples and places of worship, meaning that these new buildings were still considered sacred to the indigenous people. The Spanish strategy of attempting to remove and replace indigenous belief systems with a Spanish Catholic one was not totally successful, and evidently there were compromises in most aspects of culture: not only in art and fashion, but in the religious ideas and figures themselves.

The subjects of the àngeles arcabuceros – the angels themselves – are incredibly important in exploring the cultural balance between the Spanish and the Inca. One possible theory as to why the Inca painted Catholic angels as armed white men is that when instructed by the missionaries to depict Catholic angels, they had no notion of what these were supposed to look like, apart from the fact that they were powerful white men – and to colonised indigenous people, powerful white men usually take the form of men with guns. However, the angels in the paintings are specifically identified as Asiel, Letiel and Eliel: these are non-Biblical archangels who originate from the apocryphal pre-Biblical texts such as the Book of Enoch. In the medieval period there had been a Catholic interest in studying the Hebrew names of apocryphal archangels under the assumption that these would bring one closer to God; this tradition was condemned by the Council of Trent, who ruled that the only three canonical archangels were to be Michael, Gabriel and Raphael. However, Ramon Mujica Pinilla suggests that ‘this prohibition was definitely never observed in Baroque Spain or Viceregal Peru, where painted series of angels, singled out by name, arrived from Madrid and Seville,’ and Kelly Donahue-Wallace concurs, writing ‘church authorities condemned apocryphal archangels, but Latin American artists did not desist.’ The Spanish monarchy was fascinated by the concept of a whole army of apocryphal archangels and interpreted them as a religious army, conflated with Spain’s actual army, lending them religious power in Europe. The Book of Enoch ‘was known in Peru through Athanasius Kircher’s encyclopædic Oedipus Aegiptiacus, […] which enshrined the common agenda of the Austrian Hapsburgs and the Jesuit order to decipher the hieroglyphs of ancient Egypt, Hermeticism and the Hebrew Cabbala – including the study of the secret names of angels revealed to the Hebrew prophets – as a basis for a new imperial and universal cosmology.’ This Spanish fascination with traditional Jewish mysticism seems counterintuitive from a nation that persecuted Jews through institutions such as the Spanish Inquisition, yet the practice evidently made its way to Peru and manifested in the art of the local people, portraying the apocryphal archangels that so intrigued the Spanish Catholics but were condemned by the Romans. In around 1647, Spain sent a series of religious paintings to Lima, painted by none other than Francisco de Zurbaran; Mujica Pinilla writes that ‘at the foot of each image a scene was depicted which associated each angel with the Old Testament prophet to whom he had appeared, thus showing the relevance of Hebrew angelology among the religious orders of Viceregal Peru.’

Aside from the pre-existing Spanish interest in the apocryphal angels, there are other theories as to their prevalence in Inca art, directed and influenced by the Spanish missionaries. Undoubtedly, ‘the intention of this type of representation was to establish a bridge between the worship in pre-Hispanic Peru of winged deities and the religion imposed upon the indigenous population by the Spanish.’ The àngeles arcabuceros are young and androgynous: Catholic doctrine taught that angels were male, yet the Inca worshipped deities of multiple genders, and so the ambiguous gender of the angels allowed both parties to project their ideas of angels onto the paintings. The fact that these angels were not Biblical canon possibly made it more acceptable to the Spanish for the Inca to ‘corrupt’ Christian iconography by painting them as Andeans and mapping their own deities onto the Christian ones. The angel Eliel specifically is ‘depicted in Aramaic texts as a spirit invoked through magic rituals,‘ thus making the figure more recognisable and accessible to indigenous cultures, in which magic and spirits featured heavily. More generally, the images of winged angels with guns evoked images of pre-existing Inca deities: ‘the natives associated the harquebus with Illapa, their old god of thunder and lightning.‘ Aside from their adaptability as non-canonical Christian angels, the imagery of armed angels was essential to the Spanish narrative of themselves as a conquering army of God ‘seeking to renew the ideals of the age of the apostles, but one set within an expansionist discourse marked by spiritual and temporal tutelage.’

The àngeles arcabuceros are only a small part of the wider Hispanicisation of Andean culture. As Beaule writes, aside from art, the Spanish also imported aspects of European ‘civilisation’ such as architecture, clothing and of course, religion, but they primarily achieved this through an assimilation or ‘hybridisation’ of Spanish and Inca culture, as opposed to a complete erasure of the latter. Dean and Leibsohn describe the term ‘hybrid’ in this context as ‘things that were newly, and partially, European, distinguishing these works from objects and practices with either longer European histories […] or no European histories at all. Further, hybrids were things that Europeans did not (or could not) successfully incorporate or co-opt:’ crucially, that this new culture was not a corrupted version of Spanish culture, but a new, unique and free-standing culture whose legacy persists today, through its art, dress and religious beliefs. Furthermore, perhaps the reason that this new ‘hybrid’ culture was so quickly cultivated in Viceregal Peru stems from the Inca belief in ‘asymmetrical dualism’ – the belief that reality, and therefore culture, is built by forces that are different and unbalanced, but need each other to be complete. This phenomenon can be seen in most aspects of colonial Andean culture: the clothes of the angels which elegantly combine traditional dress with Spanish imports; the styles of art from different cultures and nations brought together in one genre of painting; and the religion itself, the assimilation of winged Inca deities with pre-Biblical Abrahamic archangels which were acceptable to both missionaries and the indigenous population.

Bibliography

Carolyn Dean and Dana Leibsohn, ‘Hybridity and Its Discontents: Considering Visual Culture in Colonial South America’, Colonial Latin American Review (2003)

Anonymous, ‘Archangel Eliel with Harquebus’, MALI, Museo de Arte de Lima, Google Arts and Culture (https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/archangel-eliel-with-harquebus-anonymous-cusco-school/OAG86bQ16mtHvQ?hl=en) [date accessed: 08/06/2020]

Ramon Mujica Pinilla, ‘Angels and demons in the conquest of Peru’, Angels, Demons and the New World (Cambridge University Press, 2013)

Kelly Donahue-Wallace, Art and Architecture of Viceregal Latin America, 1521-1821 (University of New Mexico Press, 2008)

Kate E Holohan, Andrew W. Mellon, ‘Hanging (?) Fragment’, The Met 150, 2016 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/320804 (date accessed: 07/06/20)

Ann Sutherland Harris, Seventeenth-century Art and Architecture (Laurence King Publishing, 2005)

Jacob de Gheyn II, Wapenhandelinghe van Roers Musquetten ende Spiessen (Amsterdam, 1607)

Nina Lamal, ‘Publishing Military Books in the Low Countries and in Italy’, Specialist Markets in the Early Modern Book World (Brill, 2015)

Alicia Marta Seldes, ‘A Note on the Pigments and Media in Some Spanish Colonial Paintings from Argentina’, Studies in Conservation, Vol. 39, No. 4 (Nov. 1994)

Alphonso Lingis, ‘Chapter One: Angels With Guns’, Rendezvous with the Sensuous: Readings on Aesthetics (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014)

Christine Beaule, ‘Andean clothing, gender and indigeneity in Colonial Period Latin America’, Critical Studies in Men’s Fashion, Vol 2, No. 1 (University of Hawai’i, 2015)