The image of the Biblical heroine Judith beheading the tyrant Holofernes is an enduring one in Italian Renaissance art. The unique subject of female violence, so different from portrayals of the virtuous Virgin Mary or coy Eve, was portrayed by many artists across the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, spanning different artistic periods from Mannerism to Baroque. Naturally, with such artistic and chronological variation, each version of the image is distinctive and different, though the key elements of the tale remain the same: the righteous Judith and the head of the vicious tyrant Holofernes, often accompanied by her loyal maidservant. However, one of the earlier paintings of the subject, completed by Antonio Allegri da Correggio, more commonly known as Correggio, is set apart in how it conveys the Biblical story.

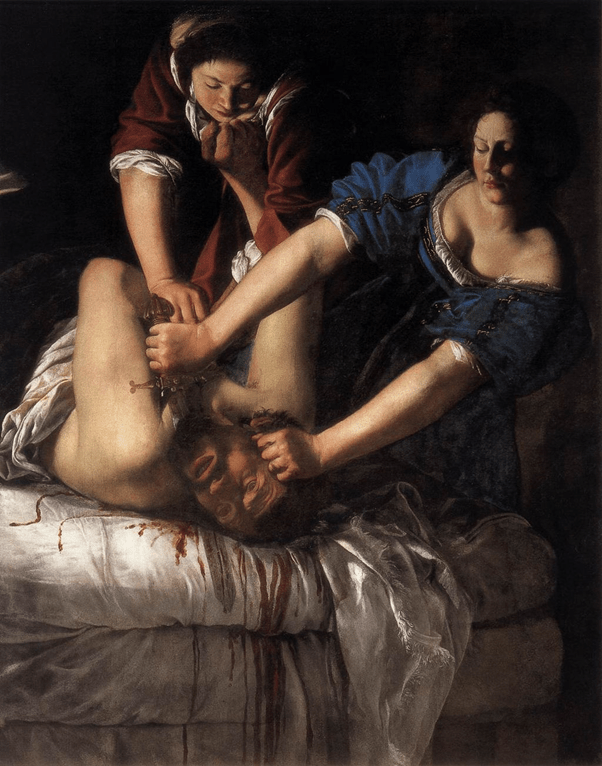

Correggio’s Judith stands to one side in the painting, dressed in pale gold silks customary for a wealthy Renaissance lady. Her hair falls in golden ringlets and her face is placid and serene as she watches, almost as a spectator, Holofernes’ head being placed into a sack. A viewer of the painting would be forgiven for thinking it was not Judith’s hand placing it there: Correggio uses masterful chiaroscuro to create a dark shadow down the centre of the painting, separating Judith from her maidservant, the disembodied head and her own hand gripping it by the hair, deliberately distancing her from the violent scene. Correggio’s portrayal of Judith as fair, gentle and tranquil is unique in a painting of the story of her brutal beheading of Holofernes, where she is normally painted as a vengeful, angry woman, such as in Artemisia Gentileschi’s 1612 painting. While he keeps the core elements of the popular story, Correggio uses his work to twist the tale, shifting much of the blame and villainy onto the maidservant, who he chose to represent as a large, squat figure with a dark complexion, wide, cartoonish features and a turban. This article will explore how this painting reflects late medieval and early Renaissance perceptions of race, and will analyse this portrayal of race and femininity alongside the dichotomy of good and evil in Correggio’s Judith and Her Maidservant.

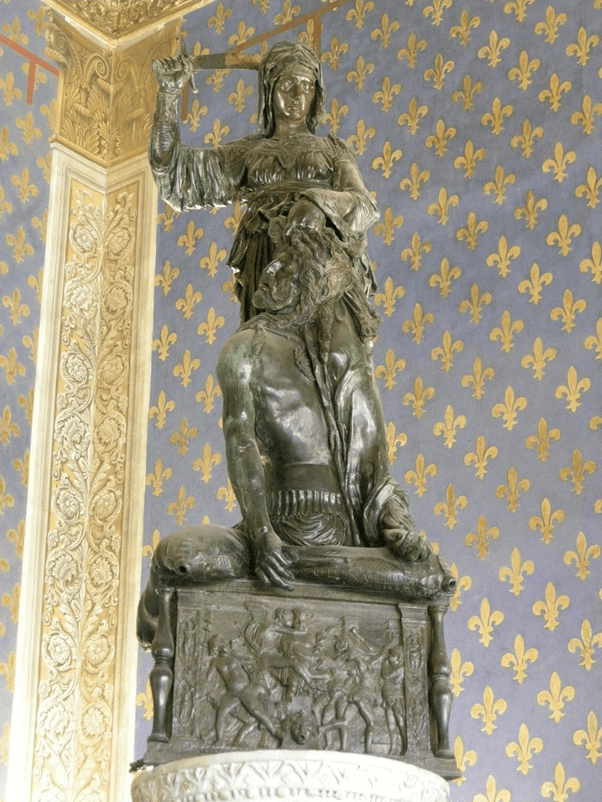

Originating in the deuterocanonical Book of Judith as a valiant Biblical heroine, Judith could be considered the epitome of the ideal Christian woman. However, not only was she, in fact, actually a Jewish woman, she was also ‘guilty of lies, seduction and terrorist murder’[3] in her slaying of Holofernes, as retribution for his destruction of her town. In painting devotional Catholic art, Correggio had to somehow reconcile the dichotomy of these violent acts and the concept of the ideal, moral Renaissance woman. Although the Florentine Senate described Judith as ‘an omen of evil’ and added that ‘it is not proper that the woman should kill the male’,[4] she was still considered by many Catholics ‘exemplary as a clever and virtuous woman [who] led an ascetic life, with prayer, fasting, sack-cloth and widow’s clothing,’[5] and thus was a popular religious figure (especially in art, such as Donatello’s sculpture Judith and Holofernes [below], completed in 1464).

Roger Crum suggests that ‘fifteenth-century Florentines carefully guarded the chastity and public honour of their patrician women,’[7] indicating that the ideal Renaissance woman was demure and deferred to men, far removed from Judith’s aggressive retribution. Furthermore, Wojciechowski argues that the stories of Judith’s crimes were difficult to reconcile ‘for Christians, who recognise the commandment to love even the enemies – especially for Catholic and Orthodox Christians, who include the Book of Judith into the Bible.’[8] Correggio, then, had to accurately represent the canonical tale (lest he be accused of heresy), but importantly endear Judith to a Catholic population and reconcile her violent, acts with Christian teachings. In Judith and Her Maidservant, he achieves this by not only portraying her as a fair, well-dressed and serene Renaissance lady, quietly standing to one side as her maidservant grimaces over the disembodied head, but by removing her innate Judaism and white-washing her character. When the painting was completed in 1514, the Spanish Inquisition, an anti-heretical witch hunt in nearby Spain, was in its thirty-sixth year of operation, and had ordered an expulsion of Spanish and Portuguese Jews around 20 years before.[9] Anti-Semitism was rife across medieval Europe and so it was typical for Biblical figures to be white-washed and Christianised. Judith, originally from the Biblical Middle Eastern city of Bethulia,[10] is painted with golden curls and fair skin, in sharp contrast to the dark complexion and wide features of her maidservant. Furthermore, Correggio’s white-washing is particularly poignant in his portrayal of Judith: Ciletti argues that ‘Judith saved her people by vanquishing an adversary she described as not just one heathen but ‘all unbelievers’: she thus stood as an ideal agent of anti-heretical propaganda.’[11] In Judith’s role as enemy of heresy, then, she could not possibly be portrayed as a Jewish figure, considered by medieval Christians as the epitome of heretical thought. Dana E. Katz agrees with this concept of Renaissance artists using their work to remove Jewish influence in the sixteenth century, arguing:

‘Renaissance paintings have significant heuristic value to Jewish historiography as integral components of the sociopolitical and religious infrastructure of Renaissance Italy. Such paintings functioned as a mechanism of social distinction that legitimised and universalised Christian powers in general.’[12]

Dana E. Katz, The Jew in the Art of the Italian Renaissance (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008) p. 15

Not only did Correggio remove any non-white ethnic or religious features of Judith; he also had to complete this narrative of equating good versus evil with white versus non-white, and he did this by deliberately coding the maidservant as ‘exotic’. With his gentle, white Judith seeming to be a blameless spectator of her own violence, the villainy of the narrative had to be shifted elsewhere, and the maidservant was an ideal canvas on which to paint racialised medieval ideas of good and evil. The unnamed maidservant is deliberately exoticised, with her wide, cartoonish features, dark skin and turban, yet her exact ethnicity is left vague, underlining its unimportance to the artist. The emphasis in the painting is not on giving the maid a specific cultural background, but on highlighting her non-whiteness: Judith, the beautiful, Christianised heroine could not possibly get her hands dirty with murder, so Correggio paints a caricature of an ‘ugly’ non-white, lower class woman to bear the brunt of the sin for her. This racialisation of the characters is crucial to the narrative Correggio constructs through the painting: Nelson argues that where ‘colonial discourse has linked blackness to animalism, sexual deviance and evolutionary inferiority, whiteness has been associated with humanity, civilization and an essential superiority’:[13] in essence, it is the contrast in the two women’s races that solidified the dichotomy of good and evil for a contemporary Renaissance audience. Though historian G.V. Scammell argues that anti-Black racism did not reach its peak in Europe until the mid-sixteenth century, he acknowledges that:

‘Antiquity taught that black meant depravity and in early Christian tradition it stood for all that was ugly and revolting. It represented evil and corruption in medieval popular culture, and by the sixteenth century it was understood that Africans were black because of the enormity of the sins of their ancestors.’[14]

G. V. Scammell, ‘Essay and Reflection: On the Discovery of the Americas and the Spread of Intolerance, Absolutism, and Racism in Early Modern Europe’, The International History Review, 13:3, (1991) p. 508

Even if Correggio’s maidservant was not intended to be African, racist attitudes in early modern Europe extended to other cultures too: ‘chronic xenophobia, which stemmed from the survival of large and unassimilated Moorish and Jewish minorities, was intensified,’[15] as a direct result of ‘the medieval conviction that Islam was a form of Christian heresy,’[16] as seen in the Spanish Inquisition. Spanish moriscos were Muslims who had been forced to convert to Christianity only eight years before Correggio began Judith and Her Maidservant; evidently, Islamophobic sentiment was just as common as antisemitism.[17] Again, however, Correggio simply assigns the maidservant the vague identity of ‘non-white’: as Scammell remarks, ‘the great majority of Europeans who penetrated to the wider world, or who knew anything of it, rapidly came to the view, expressed in a rich vocabulary of abuse and manifested in gratuitous insult and hostility, that the rest of the globe’s inhabitants were of little merit.’[18] Her race does not matter: the character is merely used as an intertextual symbol of evil and villainy which would have been understood by most of sixteenth-century Europe, and makes her the perfect vehicle for blame for Judith’s brutal slaying of Holofernes.

In his work Judith and Her Maidservant With the Head of Holofernes, Correggio deliberately racialises the subjects in an attempt to reconcile the idea of a Biblical heroine committing a violent act, by maintaining the titular heroine’s innocence and virtue, and shifting the guilt and violence towards the non-white servant. Through this racialised portrayal of good and evil, Correggio’s work belies early Renaissance attitudes about race, morality and heresy, and European perceptions of white supremacy, which would solidify themselves over the coming decades as colonialism and expansionist policies. Perhaps art historian Sister Wendy Beckett captured Correggio’s Judith best when she described it as a ‘schizophrenic picture, a strange tribute to the desire to see all in black and white.’[19]

[1] Figure 1: Correggio, Judith and Her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes (1510-1514), oil on panel, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Strasbourg

[2] Figure 2: Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Slaying Holofernes (1612-13), oil on canvas, Museo Capodimonte, Naples

[3] Michał Wojciechowski, ‘Moral Teaching of the Book of Judith’, A Pious Seductress: Studies in the Book of Judith (Berlin/Boston: de Gruyter, 2012) p. 86

[4] Elena Ciletti, ‘Patriarchal Ideology’, p. 68, citing the translation in Robert Klein and Henri Zerner (eds.), Italian Art (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1966), p. 41

[5] Wojciechowski, ‘Moral Teaching of the Book of Judith’, p. 88

[6] Figure 3: Donatello, Judith and Holofernes (1457-1464), bronze, Palazzo Vecchio, Florence

[7] Roger J. Crum, ‘Judith Between the Private and Public Realms in Renaissance Florence’, The Sword of Judith: Judith Studies Across the Discipline (Kevin R. Brine, Elena Ciletti and Henrike Lähnemann [eds.]) (Cambridge OpenBook Publishers, 2010) p. 291

[8] Wojciechowski, ‘Moral Teaching of the Book of Judith’, p. 86

[9] Gretchen D. Starr-Lebeau, ‘Jews, Expulsions of (Spain; Portugal),’ Europe, 1450 to 1789: Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2003) p. 274

[10] Marcus Jastrow and Frants Buhl, ‘Bethulia (Bαιτουλοόα, Bαιτουλία, Bετυλοόα, Bαιτυλοόα; Vulgate, Bethulia),’ The Jewish Encyclopedia. (Funk & Wagnalls, 1901-1906) [http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/3228-bethulia] date accessed: 16/11/20

[11] Elena Ciletti, ‘Judith Imagery as Catholic Orthodoxy in Counter-Reformation Italy,’ The Sword of Judith: Judith Studies Across the Disciplines (Kevin R. Brine, Elena Ciletti and Henrike Lähnemann [eds.]) (Cambridge OpenBook Publishers, 2010) p. 345

[12] Dana E. Katz, The Jew in the Art of the Italian Renaissance (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008) p. 15

[13] Charmaine A. Nelson, Representing the Black Female Subject in Western Art, Taylor & Francis Group, 2010. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/warw/detail.action?docID=537896 [date accessed: 16/11/20]

[14] G.V. Scammell, ‘Essay and Reflection: On the Discovery of the Americas and the Spread of Intolerance, Absolutism, and Racism in Early Modern Europe’, The International History Review, 13:3, (1991) p. 508

[15] Ibid. p. 515

[16] Todd H. Green, The Fear of Islam, Second Edition: An Introduction to Islamophobia in the West, (Fortress Press, US, 2015)p. 41

[17] L. P. Harvey, Muslims in Spain, 1500 to 1614. (University of Chicago Press, 2005) p. 14

[18] Scammell, ‘Essay and Reflection’, p. 506

[19] Sister Wendy Beckett, Sister Wendy’s 1000 Masterpieces (Great Britain: Dorling Kindersley, 1999) p. 97